Jacqui Symons: Artist + Creator of Slow Lane Studio

Following the practice of cultivating and experimenting with plants as a source of colour, Jacqui Symons founded Slow Lane Studio to focus on environmentally responsible methods for printing, dyeing and colouring. She established the studio based on her research into plant-based pigments and natural dyeing techniques, and now shares this knowledge through hosting workshops that offer practical advice and make this information more accessible. By exploring slow production that reduces consumption and waste, Jacqui’s work encourages artists to consider and reflect on the materials that they use, and inspires them to create their own from plant-based sources.

In the discussion below, she reveals the origins, insights and experiences behind Slow Lane Studio:

Jacqui Symons at her studio, Llandeilo

Photograph by Richard Sturges

Can you share the story of how you connected with natural dyeing? Was there a specific moment you can recall, or was it a steady development?

I’ve told this story many times before as it is a particularly strong memory for me and there was such an ‘aha’ moment…

In 2018, I was in Canada completing a month’s printmaking residency at Kingsbrae Botanic Gardens when a local artist asked me if my oil-based inks were environmentally-friendly. At that time I didn’t know and, looking back, this now seems so shocking to me. For the previous two years, I had been creating work for a major exhibition about climate change, loss of biodiversity and nature and hadn’t thought once about where my art materials were coming from.

This started me on a journey into using plant-based colour for printmaking: I learnt how to make printmaking inks, how to extract colour from plants and make it useable in oil-based carriers, I learnt about natural colour and science and dye plants – it was a steep learning curve! I began to realise there was a whole other world connected to natural colour that I hadn’t really considered, of natural dyeing and colouring fibres of yarns and fabrics, and it was here that I met and trained with Jenny Dean, who has become a great friend and mentor.

Your work seems to be a collaboration with the natural world, how would you describe your relationship with the plants you work with?

I find plants wonderful, complex and mysterious; to me a never-ending source of interest and inspiration, not just in the colour they might hold but also in their shape, their habits and how they have evolved. I love that many dye plants don’t reveal the dyes and pigments contained within; the blue of indigo hidden in green leaves or the bright reds, pinks and purples in the roots of the invasive, scrambling and not particularly beautiful, madder plant.

I find there is a quiet dialogue in working with plants, the seasonal ebb and flow of growth, harvest and a winter hibernation influences my work and encourages a thoughtfulness and contemplation that can be easily forgotten in the daily rush of emails, social media and administration.

For me, plants have very much been a gateway into the rest of the natural world - the interconnectedness of everything astounds me, for example, the mycorrhizal network of trees and how they communicate or the way some plants have evolved to be pollinated by a specific insect.

Natural Dye Samples

Photograph by Richard Sturges

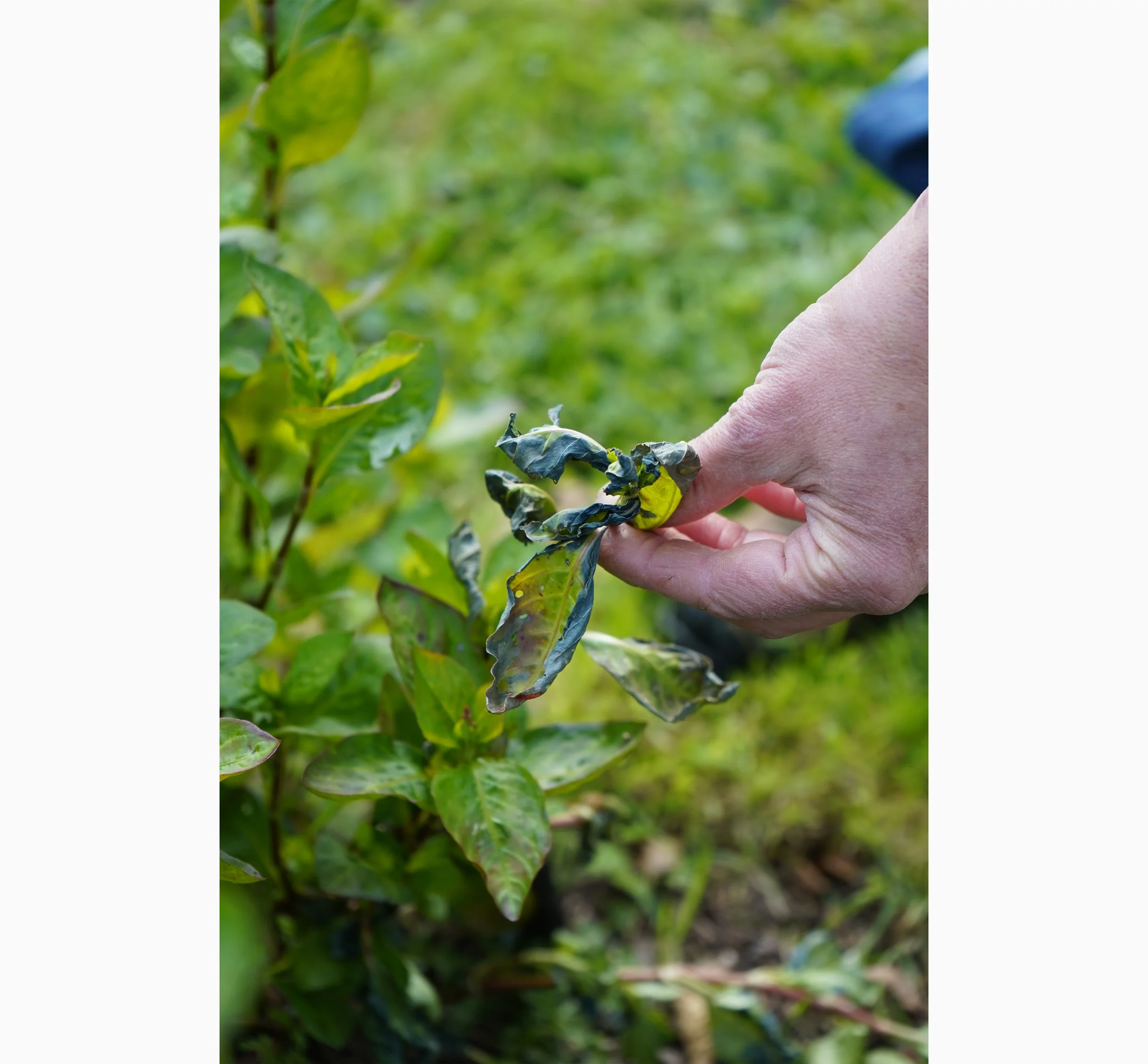

Is there any plant in particular that has been challenging to work with, and is there anything you have learnt from the experience?

When working with plant-based colour, each plant can have it’s own challenges or characteristics and these can change depending on what you are using it for but also from individual plant to individual plant - soil type and health, weather, amount of water and location of the plant can all affect the colour and the amount of pigment it contains. This is part of the joy in working with natural materials – it forces a deeper relationship and understanding of the colours being used. Plant-based colour is not an ‘off-the-shelf’ synthetically manufactured product and that is kind of the point, it’s a living product that has unique tones and hues within each extraction.

However, my current challenge is with indigo and specifically extracting the pigment. The nuance and finesse required to successfully extract a good blue pigment is a challenge and the process benefits from experience and knowledge. Whilst general recipes are available, so much depends on observing your plants and the development of the colour during an extraction, I feel I am a long way from the supposed 10,000 hours required to master a skill. For me, that’s okay – an acceptance that things go wrong and a willingness to keep trying and exploring is important. Though to be clear I’m not floating on a cloud through each day – there is quite often swearing, self-doubt and disappointment!

Persicaria Tinctoria (Indigo)

Photograph by Richard Sturges

The pigment garden and plant pigment library that you have cultivated appears to be a project that involves constant discovery. Do you have any personal anecdotes of any unexpected or accidental discovery while experimenting with a plant?

Yes, that you can print with pollen! Early on in my natural colour journey and whilst out on a walk in early Spring, I brushed past a goat willow (Salix caprea) tree densely covered with flowers and was interested to see my black coat turn bright yellow with pollen. I collected some flowers, let them dry slightly then separated the pollen by shaking in a fine-meshed sieve. The bright yellow pollen was incredibly fine, just like a well-ground pigment so I decided to try and make some oil-based printmaking ink with it. I ended up with a yellow ink that, whilst not perfect, printed well and smelled amazing.

I believe this ‘beginner’s mindset’ of just trying something out is an incredibly important and useful approach, something to try and retain as you become more experienced in your field. It can be very easy to rely solely on accepted knowledge and opinion but challenging and questioning work and processes is part of my approach, retaining a natural curiosity and lack of preconceptions. I want readers to do this with my book – experimenting with recipes, changing ratios of ingredients, adopting a ‘what happens if I do this?’ methodology. Use the recipes and processes as a starting point for your own practice and development.

Your study and experimentation with plant materials is central to your visual legacy, are there any feelings you hope to evoke with the colours you create?

I want people to have a deeper appreciation for nature, to be truly amazed at the colours that can be extracted from plants and for people to experience the same wonderment that I experience on a regular basis. I love running natural dye workshops and courses for the very real reactions that students have on seeing yarns and fabrics come out of the dye pot for the first time. There is always lots of ‘oohs’ and ‘aahs’, which is very gratifying but also reinforces my belief that natural colours are superior to anything synthetic. A few years ago at an indigo-dyeing workshop, one attendee, on seeing the green fabric turn to blue as it was drawn from an indigo fructose vat, commented “that’s magic” was followed by another comment “no, that’s science”. I think it’s probably a little bit of both…

Jacqui Symons at her studio, Llandeilo

Photograph by Richard Sturges

Plant-based Pigments (Madder)

Photograph by Richard Sturges

The crafting of natural dyes is an inherently slow process of production. What is your perspective on how your work in natural dyeing fits into a broader conversation on sustainable production?

I would hope that my work brings attention to the power and beauty and strength of natural colour and, at the very least, makes people consider it as an alternative to synthetic options.

I recently read that about 100 billion items of clothing are made each year yet there are already enough clothes in the world to dress the next six generations of people. That means that if we stopped making clothes today, completely, no new items would need to be made until the year 2175, which is a bit mind-boggling, to be honest. Whilst this is obviously not going to happen, it is a stark reminder of our over-consumption and this is something I struggle with when making new work or creating products be they clothing, yarns, fine art prints or pigments.

I have been working on creating an art installation of a clothes collection that is secondhand, made of natural fibres and have all been naturally-dyed or printed by myself. The clothes would be labelled with the true cost of producing them; including my time, the dyes and mordants needed, the amount of water required, the energy used and how much they cost to buy secondhand, in an attempt to promote the use of natural dyes and make it a viable option for colouring our clothes.

What’s your favourite colour and why?

I don’t have a favourite colour anymore but I do have a favourite dye plant – madder. Known as the queen of dyes, it is a continuous source of surprise and awe for me. The range of colours you can create from madder including reds, purples and pinks through to browns and oranges is just brilliant and, in my opinion, knocks the socks off of any synthetic dye, paint or pigment. If you force me to answer, maybe it’s red but you can keep your cadmiums, vermillions and crimsons, I’m sticking with marvellous madder.

Madder

Photograph by Richard Sturges