Indigo: A Colour Shaped by History

Indigo carries a rich history. Unlike most colours that come from natural dyes and have been substituted by synthetics, Indigo is still used for dyeing fabrics in the 21st century.

Rich history of Indigo

Indigo is one of the rarest colours in the world. Since ancient times, it has been harvested from the leaves of little shrubs (Indigofera) and was considered one of the most valuable pigments in the world. Over the century, indigo held colossal religious, cultural, trade and artistic value. Across different cultures, it symbolised sky, priestliness, power, and infinity.

Indigofera tinctoria

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the Middle Ages, indigo became known as ‘blue gold’. It was traded across the Sahara, the Mediterranean and Europe. It supplanted European woad (Isatis tinctoria) due to Indigo’s colour depth and durability. People used indigo in various ways: to dye fabric and their hair, as a remedy, cosmetics and even as magical protection. African women played a significant role in keeping these traditions and building social and economic power around indigo.

But Indigo also played a significant role in fuelling both slavery and colonialism. It was cultivated under duress in Africa, India, and America. We have an article tracing indigo’s journey from a symbol of colonial oppression to one of cultural revival and sustainability, which you can read here. In South Carolina, this natural dye became a main plantation crop, bringing millions of profits.

Despite economic decline following the invention of synthetic dyes, indigo left a deep imprint on world culture. It influenced artists, writers, and musicians such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Henri Émile Benoît Matisse and inspired American jazz and blues.

Chemistry of Fermentation

Indigo, along with rice, became one of the main crops of South Carolina in the 18th century. The weed was often planted in rice fields where rice wouldn’t grow, allowing plantations to combine the cultivation of two profitable crops. This system maximised the use of slave labour without changing the structure of farms. Indigo was highly valued by the British imperial market, which sought to reduce dependence on imports.

High demand for natural dye stimulated the mass use of slave labour: ‘Indigo became a significant export for the region, and enslaved people in South Carolina were forced to labour year-round to meet production demands’ (The Carolinas - the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 2022).

The processing of indigo was incredibly demanding. Before indigo acquires its signature hue, freshly cut leaves in South Carolina had to be covered in water and left to ferment in giant wooden vats. The process took two to three days and required constant tending. In unsanitary, hot conditions, which contributed to illness and death among enslaved people.

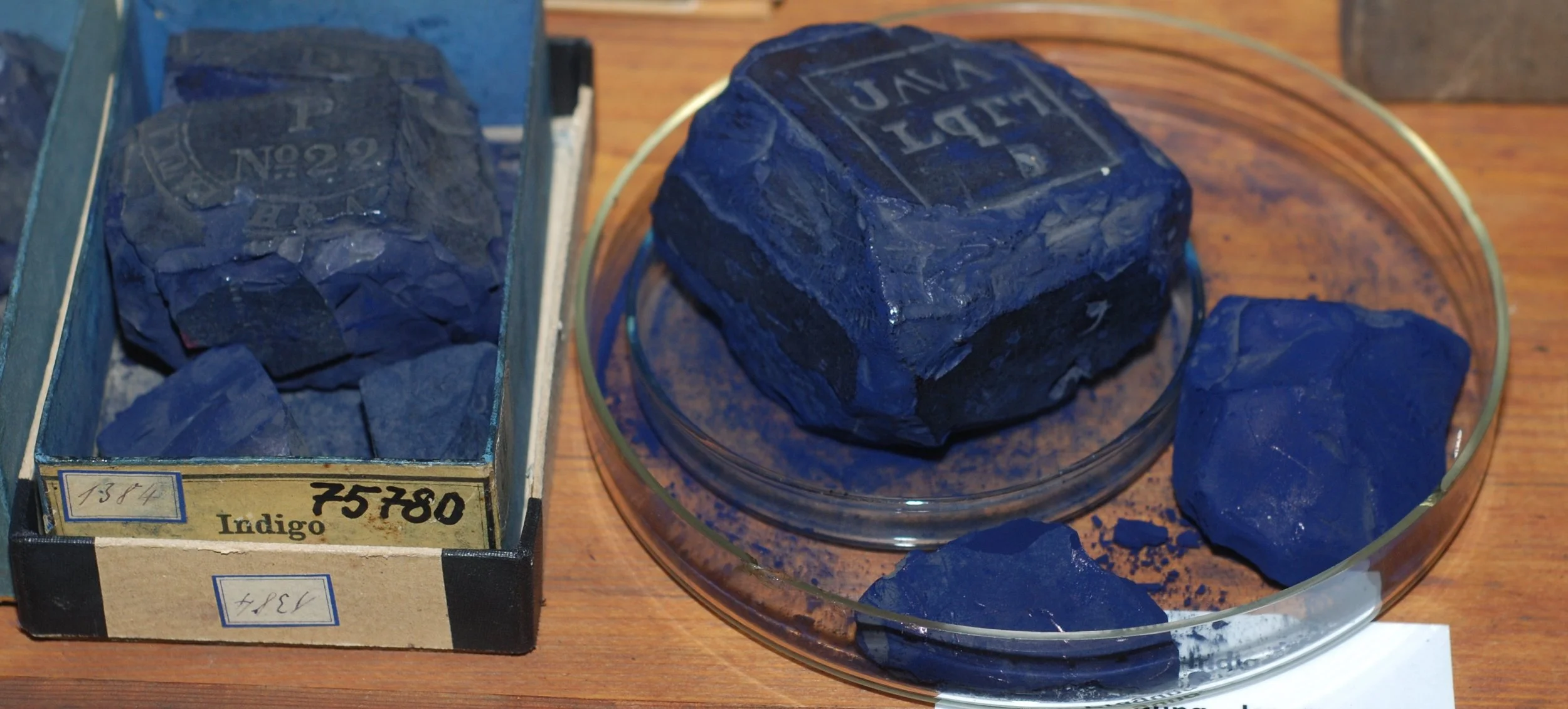

Indigo, historical dye collection of the Technical University of Dresden, Germany

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In Africa and Asia, another method was used. The greens were pounded and pressed into spheres. Once dry, the balls were mixed with water that had been filtered through ash from burning green wood. After a few days of fermentation, the strong smell and foaming surface of the mixture showed that it was ready to be dyed.

During fermentation, enzymes break down the natural substance indican into a colourless compound. When this compound collides with air, oxidised indican changes into the blue dye indigotin. At the same time, another substance, indirubin, is sometimes formed. This is a reddish pigment, considered a by-product.

Structure of indigo dye - indigotin (C₁₆H₁₀N₂O₂)

British North America and Slave History

South Carolina was the first British North American colony founded explicitly as a 'slave society.' Its founders granted settlers absolute power over enslaved Africans and offered land for every enslaved person owned. To satisfy the demand, traffickers imported huge consignments of Africans, generating enormous profits. Between the 16th and mid-19th centuries, at least 150,000 African people were transported through South Carolina.

After the crop was introduced in the 1690s, human traffickers in the Lowcountry began to purchase large numbers of enslaved Africans from the rice-growing communities of West Africa. Colonists expanded plantation territory, establishing Beaufort in 1711 and Georgetown in 1729.

The slave trade was so prevalent in South Carolina that, by the 1720s, the Lowcountry’s population of enslaved people exceeded that of white colonists. Many newly arrived captives were taken to quarantine camps called 'pest houses' on islands like Sullivan’s, Morris, and James. Tens of thousands passed through these sites, where the conditions were so horrific that Morris Island became known as 'Coffin Island.'

North Carolina Trafficking

Ports in North Carolina grew more slowly because the geography was hostile to trafficking. As a result, many enslaved Africans in North Carolina were brought from South Carolina or Virginia rather than arriving directly from Africa. In 1733, the governor of North Carolina complained that the colony received so few direct shipments that residents were forced 'to buy the refuse, refractory, and distemper’d Negroes brought in from other governments' (The Carolinas - the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 2022).

By the mid-18th century, enslavers in South Carolina were searching for a new profitable crop. They turned to indigo, a weed that produced a vivid blue dye. Indigo soon became a major export for the region, and enslaved Africans were forced to labour year-round to sustain production. All the wealth generated from indigo relied on their expertise and brutalised labour. It was enslaved Africans who cultivated the fields, endured the dangerous fermentation process, and contributed crucial agricultural knowledge without which indigo would never have succeeded.

From the mid-1740s until the Revolutionary War, indigo was a major cash crop in South Carolina. Blue was the most popular colour in Britain at the time, so indigo was exported there in large quantities, enriching plantation owners, dyers, and manufacturers. South Carolina indigo coloured most British-made blue cloth, since it was cheaper and considered 'homegrown.'

1960s: Indigo Jeans

In the 1960s, denim became a political statement thanks to civil rights activists. During the march on Washington led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., many activists wore blue denim, specifically sharecroppers’ overalls, to show how little had changed since Reconstruction. By choosing clothing associated with field labour, they highlighted the ongoing inequality Black Americans still faced. Racial equality from 1865 to 1965 made little progress; African Americans still had to wear ‘poverty clothes.’

In the 50s and 60s, denim was linked to manual labour. Most people treated it as something you wore only while doing chores at home. By wearing jeans, overalls, jackets, etc., publicly, people rebelled against being seen as slaves; it symbolised being free, but also addressed the problem of Black poverty.

The backlash showed how controversial denim still was. In 1969, around 200 students were suspended for wearing dark blue pants because they resembled denim too closely. And within many Black communities, people refused to wear anything denim due to its history. For families who had lived through sharecropping, denim was a reminder of oppression. Cultural figures like James Brown refused to wear jeans for years and wouldn’t allow his band to wear them either. Many Black Americans who migrated North chose suits and hats for factory work to visually distance themselves from the rural South and the clothing associated with forced labour.

By wearing denim publicly, civil rights activists were reclaiming something that had previously been used to identify, control and demean Black people.

Bibliography

Indigo in the fabric of Early South Carolina | Charleston County Public Library (no date). https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/indigo-fabric-early-south-carolina.

Indigo: plant of culture and color (2024). https://cornellbotanicgardens.org/indigo-plant-of-culture-and-color.

Komar, M. (2017) 'What the civil rights movement has to do with denim,' Racked, 30 October. https://www.racked.com/2017/10/30/16496866/denim-civil-rights-movement-blue-jeans-history.

McKinley, C.E. (2011) Indigo: In search of the color that seduced the world, Medical Entomology and Zoology. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB12125616.

Origins - The Transatlantic Slave Trade (2022). https://eji.org/report/transatlantic-slave-trade/origins/#the-barbarity-of-the-middle-passage.

Images

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Indigofera_tinctoria_L._(50348009148).jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Indigo-Historische_Farbstoffsammlung.jpg

Cover Image

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Indigo-guizhou.jpg